Class Meeting 18 (4) Functional programming in R: Part II

library(tidyverse)

library(rlang)

library(glue)

#install.packages('docopt')

#install.packages('testthat')

library(docopt) # you will need to install this using install.packages('docopt')

library(testthat) # you will need to install this using install.packages('testthat')18.1 Today’s Agenda

Announcements:

- If you need Git help, please come to our office hours! This is a crucial concept and it’s worth getting it right!

- Your project repos should be public, assignment and participation repos are private

- Apologies if I mis-spoke and for any confusion. See GitHub issue for more

- Next Thursday’s class

- Part 1: Running Rscripts from the terminal/command prompt (20 mins)

- “REPL” vs. non-interactive scripts

- Converting interactive R code to a scripted, non-interactive version

- Part 2: Command-line arguments and docopt (30 mins)

- Motivating command-line arguments

- Options for specifying command-line arguments

- Adding command-line arguments to your R scripts

- Part 3: Writing tests for your functions (25 mins)

- Motivating the use of tests in programming

- Introducing the

testthatpackage - Writing tests using the

testthatpackage

18.2 Learning outcomes for this lecture

- Evaluate when it is optimal to code in a REPL framework (interactively) vs. using scripts.

- Demonstrate the ability to run interactive R code from a .R script.

- Use principles of functional programming to create functions inside R scripts.

- Explain the purpose of command-line arguments and describe the various flavours (optional, required, long and short forms, repeating, etc…).

- Use the

docoptto create commandline arguments for R scripts. - Defend the use of tests when programming.

- Use the

testthatlibrary to write tests for R functions.

18.3 Part 1: Running Rscripts from the terminal/command prompt (15 mins)

This section has been adapted from Tiffany Timbers’ DSCI 522 lectures found here.

18.3.1 “REPL” vs. non-interactive scripts

So far in STAT 545 and 547M, we have only been working on Rmd files and interactively working with code. We run and re-run specific code chunks, add bits of code, and re-run it to get updated results. Of course, this works - but is it reproducible ? Can you trust that in a week, or a month, or a year from now that you will be able to reproduce the exact steps needed to get the same answer? Usually not. The above style of working actually has a name: REPL, or Read-Evaluate-Print-Loop. Despite the fact that it’s usually not easily reproducible, it is actually VERY useful! It’s good for:

- solving smaller problems in projects limited in scope

- explore and play around with unfamiliar and unknown datasets

- developing code that will eventually make its way into a script or turned into a function

- developing code that you will only use once

It is rare that data scientists would go directly towards creating scripts and functions without first developing them in a REPL environment.

At this point, you may be wondering what scripts are and why we should write them?.

Well, an R script is just a text file that contains R code that is run in a sequence, usually with no or minimal intervention from the user.

Scripts are generally run from the Terminal, but can also be run from IDEs (interactive developer environment; RStudio is an IDE) and even the Rconsole using source(script_name.R).

As for why:

- Scripts are generally more time efficient (especially for long term usage)

- You can combine multiple scripts to create an analysis pipeline (next week!)

- Scripts can be reused and adapted for different purposes; additional functionality can be added to scripts without removing the ability of it working for previous analyses

- Are an important component of reproducible workflows

Alright now that we know how REPL, or interactive scripts differ from non-interactive scripts, let’s move on and actually create R scripts from interactive R code.

18.3.2 Converting interactive R code to a scripted, non-interactive version

Let’s just do a quick sanity check to make sure our script can run.

- Step 1: In the cm104 directory, create a new blank .R script and save it as

first_script.R- In RStudio, File > New File > R Script.

- Step 2: Write the following R code inside

first_script.R:print('Hello World')

- Step 3: Run the Rscript by opening a new Terminal, navigating to the directory where

first_script.Rexists and then type:Rscript first_script.R- “Hello World” should be printed to the Terminal and the R script will finish.

- Step 4: Navigate to one directory above the current directory with

cd ..- Now try running

first_script.R- does it work? - How would you modify

Rscript first_script.Rto make it work (without going into thecm104directory)?

- Now try running

## YOUR SOLUTION HERE

Rscript cm104/first_script.ROkay, let’s do something slightly more interesting: a quick demo using an interactive script that we’re going to write together.

18.3.2.1 Your Task 1:

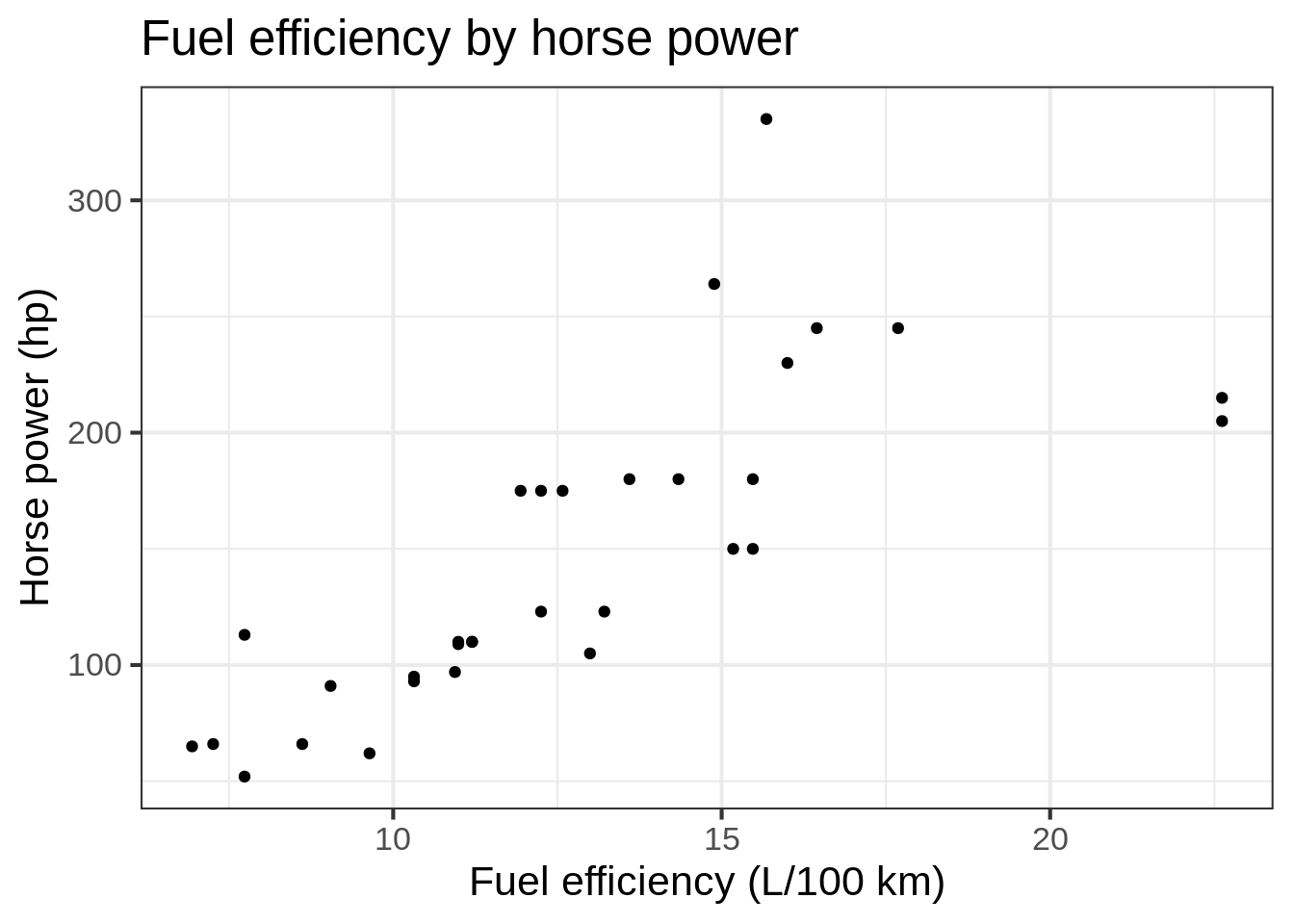

- Start with the

mtcarsdataset - Use

dplyr::mutateto create a new column for the fuel efficiency in L/100km rather than mpg - Create a plot of Horse power vs. fuel efficiency

## mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

## Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 0 1 4 4

## Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

## Datsun 710 22.8 4 108 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 1 1 4 1

## Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258 110 3.08 3.215 19.44 1 0 3 1

## Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360 175 3.15 3.440 17.02 0 0 3 2

## Valiant 18.1 6 225 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 1 0 3 1## YOUR SOLUTION HERE

mtcars %>%

mutate(lkm = 235.2145 / mpg) %>% # imperial = 282.48, #US = 235.21

ggplot(aes(x = lkm, y = hp)) + geom_point() +

theme_bw(16) + # Set font size like this

labs(x = 'Fuel efficiency (L/100 km)',

y = 'Horse power (hp)',

title = "Fuel efficiency by horse power")

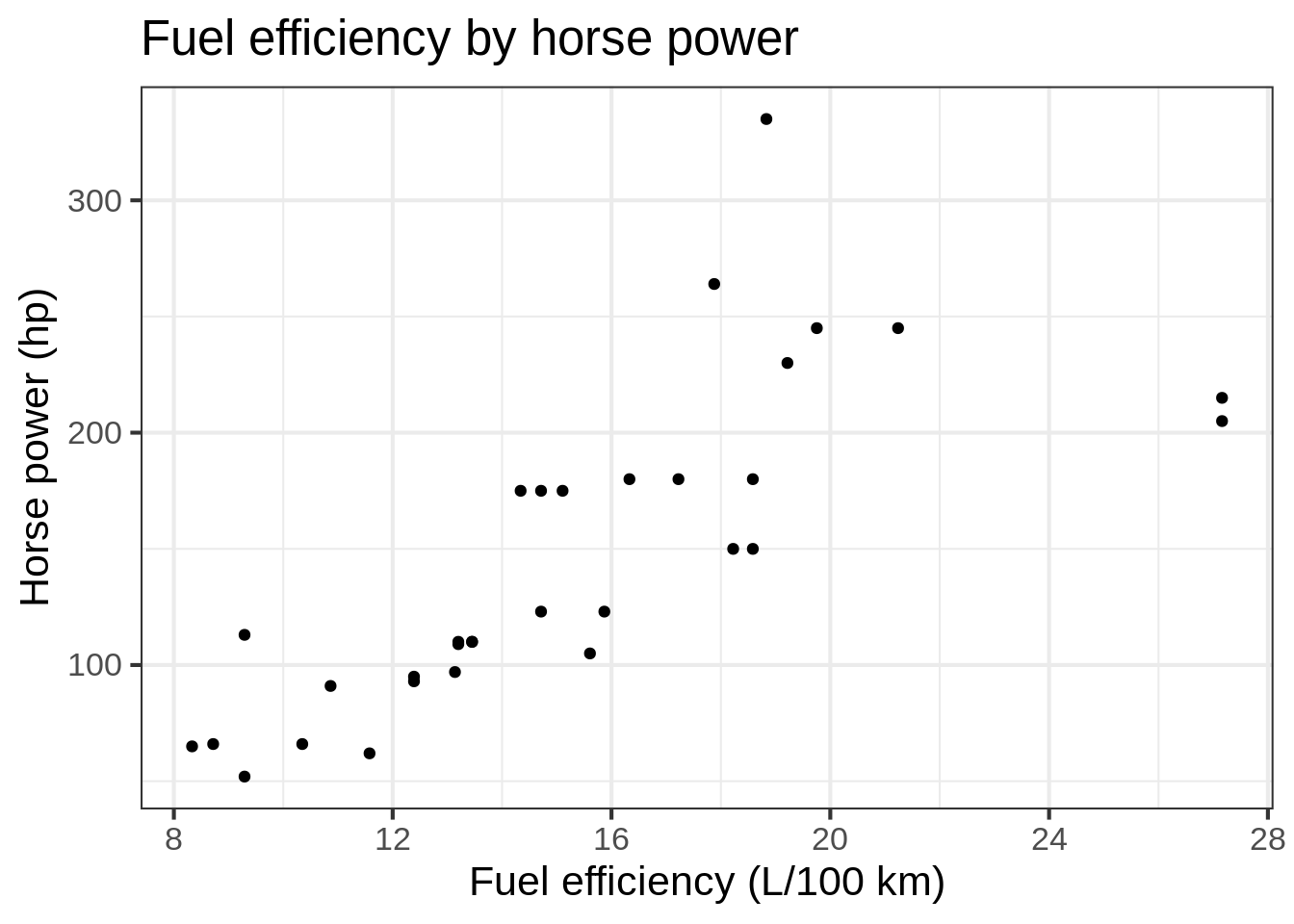

18.3.2.2 Your Task 2:

- Use the code above as a starting point

- Copy the code above and paste it into

first_script.R - Move the mutate command into a separate function

- Your function should take in a string argument with two options: “USA” and “Imperial” (set a reasonable default)

- Try running the script. Did it work? Was there a plot produced?

- If yes, great! If not, what did you have to change to get it to work?

- Can you explain why?

## YOUR SOLUTION HERE

library(tidyr)

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

fuel_conversion <- function (df, gallon_type = 'USA') {

if (gallon_type == 'USA') {

conv = 235.2145

} else {

conv = 282.48

}

df %>% mutate(lkm = conv / mpg)

}

mtcars %>%

fuel_conversion(gallon_type = 'Imperial') %>%

ggplot(aes(x = lkm, y = hp)) + geom_point() +

theme_bw(16) + # Set font size like this

labs(x = 'Fuel efficiency (L/100 km)',

y = 'Horse power (hp)',

title = "Fuel efficiency by horse power") +

ggsave('test_plot.png', width = 8, height = 5)

Great! Looks like things are working! Let’s organize our script in a slightly more useful way.

18.3.3 Structure of scripts

It is very good practice to organize the code in your script into a main function and other functions. This practice keeps your code readable and organized, this has some additional benefits we will discuss later. Here is a suggested script organization:

# documentation for how to use scripts and comments

# Load libraries and packages

# parse/define command line arguments here

# define main function

main <- function(){

# code for "guts" of script goes here

}

# Code for other functions & tests

# call main function

main()For documentation, it is suggested to use roxygen2 style.

Here is an example of this style:

#' Add together two numbers

#'

#' @param x A number

#' @param y A number

#' @return The sum of \code{x} and \code{y}

#' @examples

#' add(1, 1)

#' add(10, 1)

add <- function(x, y) {

x + y

}18.3.3.1 Your Task 3: Create a script and conform to the suggested structure

Let’s edit our script from the previous section (first_script.R) to conform to this structure.

When you’re done, paste in the contents of your script here:

## YOUR SOLUTION HERE (contents of first_script.R)

# author: Firas Moosvi

# date: 2020-03-05

"This script adds a new column to the `mtcars` dataset converting fuel efficiency from miles per gallon to Litres per 100km. This script takes the gallon_type as the variable argument.

Usage: first_script.R <gallon_type>

"

library(tidyr)

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(glue)

main <- function(gallon_type){

mtcars %>%

fuel_conversion(gallon_type = 'Imperial') %>%

ggplot(aes(x = lkm, y = hp)) + geom_point() +

theme_bw(16) + # Set font size like this

labs(x = 'Fuel efficiency (L/100 km)',

y = 'Horse power (hp)',

title = "Fuel efficiency by horse power") +

ggsave('test_plot.png', width = 8, height = 5)

print(glue("The gallon_type is ", gallon_type))

}

#' calculate fuel efficiency in L/100km

#'

#' @param df is an input of the mtcars dataframe

#' @param gallon_type is a string either `USA` or `Imperial`

#' @examples

#' fuel_conversion('USA')

fuel_conversion <- function (df, gallon_type = 'USA') {

if (gallon_type == 'USA') {

conv = 235.2145

} else {

conv = 282.48

}

df %>% mutate(lkm = conv / mpg)

}

### tests

main()18.3.4 Summary and key points of scripts

18.3.4 YOUR NOTES HERE

What if we wanted to specify the arguments of assignment to the imperial definition of gallon rather than the US one? For that, we need to look at command line arguments!

18.4 Part 2: Command-line arguments and docopt (30 mins)

This section has been adapted from Tiffany Timbers’ DSCI 522 lectures found here.

18.4.1 Introduction to docopt

We will be following the documentation for docopt here.

Key points:

- Arguments for your script can be specified by “position” or as “options”

- Options is almost always better as it allows your code and scripts to be more readable

- To allow your non-mandatory arguments use

[ ] - Use parantheses

( )for required arguments - Complex arguments can be set up using the

|(pipe) indicating “OR” as well as...to indicate repeating elements

18.4.2 Adding command line arguments in R

Let’s make our script more flexible, and specify when we call the script, whether the gallon_type is US or Imperial variable.

To do this, we use the docopt R package. This will allow us to collect the text we enter at the command line when we call the script, and make it available to us when we run the script.

When we run docopt it takes the text we entered at the command line and gives it to us as a named list of the text provided after the script name.

The names of the items in the list come from the documentation.

Whitespace at the command line is what is used to parse the text into separate items in the vector.

# author: Firas Moosvi

# date: 2020-03-05

"This script adds a new column to the `mtcars` dataset converting fuel efficiency from miles per gallon to Litres per 100km. This script takes the gallon_type as the variable argument.

Usage: first_script.R <gallon_type>

" -> doc # THIS IS NEW

library(tidyr)

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(docopt) # THIS IS NEW

library(glue)

# THIS IS NEW

opt <- docopt(doc) # This is where the "Usage" gets converted into code that allows you to use commandline arguments

main <- function(gallon_type){

mtcars %>%

fuel_conversion(gallon_type = 'Imperial') %>%

ggplot(aes(x = lkm, y = hp)) + geom_point() +

theme_bw(16) + # Set font size like this

labs(x = 'Fuel efficiency (L/100 km)',

y = 'Horse power (hp)',

title = "Fuel efficiency by horse power") +

ggsave('test_plot.png', width = 8, height = 5)

print(glue("The gallon_type is ", gallon_type))

}

#' calculate fuel efficiency in L/100km

#'

#' @param df is an input of the mtcars dataframe

#' @param gallon_type is a string either `USA` or `Imperial`

#' @examples

#' fuel_conversion('USA')

fuel_conversion <- function (df, gallon_type = 'USA') {

if (gallon_type == 'USA') {

conv = 235.2145

} else {

conv = 282.48

}

df %>% mutate(lkm = conv / mpg)

}

### tests

main(opt$gallon_type) # THIS IS NEWTo run this script from the commandline, we would open a Terminal, navigate to the directory containing the script, and run:

Rscript first_script.R 'Imperial'And that’s it!

You’ve just written your first R script with command line options!

This is a big deal!

The power you now wield is enormous!

Image obtained from Dragonball fandom here. Original copyright belongs to Dragon Ball Z © 2003 Bird Studio / Shueisha, Toei Animation. Licensed by FUNimation® Productions, Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Dragon Ball Z and all logos, character names and distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of TOEI ANIMATION.

18.4.3 Positional vs. option arguments

In the examples above, we used docopt to specify a positional argument (gallon_type).

This means that the order matters!

If we added another argument the same way we added gallon_type, the order that we specify the arguments will matter.

Our script will likely throw an error because it will try to perform the wrong operations using the wrong arguments.

Another downside to positional arguments, is that without good documentation, they can be less readable.

And certainly the call to the script to is less readable.

We should instead give the arguments names using --ARGUMENT_NAME syntax.

We call these “options”.

Below is the same script but specified using options rather than to positional arguments:

# author: Firas Moosvi

# date: 2020-03-05

"This script adds a new column to the `mtcars` dataset converting fuel efficiency from miles per gallon to Litres per 100km. This script takes the gallon_type as the variable argument.

Usage: first_script.R --gallon_type=<gallon_type>

" -> doc

library(tidyr)

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

library(docopt)

library(glue)

opt <- docopt(doc) # This is where the "Usage" gets converted into code that allows you to use commandline arguments

main <- function(gallon_type){

mtcars %>%

fuel_conversion(gallon_type = 'Imperial') %>%

ggplot(aes(x = lkm, y = hp)) + geom_point() +

theme_bw(16) + # Set font size like this

labs(x = 'Fuel efficiency (L/100 km)',

y = 'Horse power (hp)',

title = "Fuel efficiency by horse power") +

ggsave('test_plot.png', width = 8, height = 5)

print(glue("The gallon_type is ", gallon_type))

}

#' calculate fuel efficiency in L/100km

#'

#' @param df is an input of the mtcars dataframe

#' @param gallon_type is a string either `USA` or `Imperial`

#' @examples

#' fuel_conversion('USA')

fuel_conversion <- function (df, gallon_type = 'USA') {

if (gallon_type == 'USA') {

conv = 235.2145

} else {

conv = 282.48

}

df %>% mutate(lkm = conv / mpg)

}

### tests

main(opt$gallon_type)Now we would call the script like this:

Rscript first_script.R --gallon_type='Imperial'Now that the arguments have names, if we had multiple arguments, the order doesn’t matter anymore!

18.4.3.1 Your Task 4: Update the script above and add a second required argument and print it out using glue.

## YOUR SOLUTION HERE (contents of first_script.R)18.4.4 Summary and key points of options

docoptis a REALLY useful R package that allows us to easily add arguments and options to our scripts- You should always have named arguments, or options for scripts; makes your scripts much more readable

- Arguments for your script can be specified by “position” or as “options”

- Options is almost always better as it allows your code and scripts to be more readable

- To allow your non-mandatory arguments use

[ ] - Use parantheses

( )for required arguments - Complex arguments can be set up using the

|(pipe) indicating “OR” as well as...to indicate repeating elements

18.5 Quarter pole course check-in

Now that we’re roughly a quarter way through the course, I thought I’d check in to see how things are going.

Please fill out this very quick Stop-Start-Continue here so that I know what’s going well, what needs to be improved, and what requires immediate intervention.

18.6 Part 3: Writing tests for your functions

This section has been adapted from

This section is adapted from Chapter 8 of the tidynomicon textbook by Greg Wilson.

18.6.1 Testing and Error Handling

Novices write code and pray that it works. Experienced programmers know that prayer alone is not enough, and take steps to protect what little sanity they have left. This chapter looks at the tools R gives us for doing this.

18.6.2 How does R handle errors?

We say that the operation signals a condition that some other piece of code then handles. These things are all simpler to do using the rlang library, so we begin by loading that:

In order of increasing severity, the three built-in kinds of conditions are messages, warnings, and errors.

(There are also interrupts, which are generated by the user pressing Ctrl-C to stop an operation, but we will ignore those for the sake of brevity.)

We can signal conditions of these kinds using the functions message, warning, and stop, each of which takes an error message as a parameter:

## Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): This is an error.Note that we have to supply our own line ending for warnings but not for the other two cases. Note also that there are very few situations in which a warning is appropriate: if something has truly gone wrong then we should stop, but otherwise we should not distract users from more pressing concerns.

The bluntest of instruments for handling errors is to ignore them.

If a statement is wrapped in the function try then errors that occur in it are still reported, but execution continues.

Compare this:

attemptWithoutTry <- function(left, right){

temp <- left + right

"result" # returned

}

result <- attemptWithoutTry(1, "two")## Error in left + right: non-numeric argument to binary operator## Error in cat("result is", result): object 'result' not foundwith this:

attemptUsingTry <- function(left, right){

temp <- try(left + right)

"value returned" # returned

}

result <- attemptUsingTry(1, "two")## Error in left + right : non-numeric argument to binary operator## result is value returnedWe can suppress error messages from try by setting silent to TRUE:

attemptUsingTryQuietly <- function(left, right){

temp <- try(left + right, silent = TRUE)

"result" # returned

}

result <- attemptUsingTryQuietly(1, "two")

cat("result is", result)## result is resultDo NOT do this, lest you one day find yourself lost in a silent hellscape.

Should you more sensibly wish to handle conditions rather than ignore them, you may invoke tryCatch.

We begin by raising an error explicitly:

## error object is Error in doTryCatch(return(expr), name, parentenv, handler): our messageWe can now run a function that would otherwise blow up:

## error object is Error in left + right: non-numeric argument to binary operator18.6.3 What should I know about testing in general?

In keeping with common programming practice, we have left testing until the last possible moment.

The standard testing library for R is testthat and this is how tests are handled in R:

- Each test consists of a single function that tests a single property or behavior of the system.

- Tests are collected into files with prescribed names that can be found by a test runner (code that is automatically run once after each unit test).

- Shared setup (code that is automatically run once before each unit test) and teardown (Code that is automatically run once after each unit test) steps are put in functions of their own.

For now in STAT547, we will use the testthat library to test our functions in-line our Rscripts, though it is much better practice to set up your tests in a tests directory and have them run automatically.

Let’s load it and write our first test:

As is conventional with unit testing libraries, no news is good news: if a test passes, it doesn’t produce output because it doesn’t need our attention. Let’s try something that ought to fail:

## Error: Test failed: 'Zero equals one'

## * <text>:1: 0 not equal to 1.

## 1/1 mismatches

## [1] 0 - 1 == -1If you run this, you should see something like:

Error: Test failed: 'Zero equals one' * 0 not equal to 1. 1/1 mismatches [1] 0 - 1 == -1Good: we can draw some comfort from the fact that Those Beyond have not yet changed the fundamental rules of arithmetic.

But what are the curly braces around expect_equal for? The answer is that they create a code block for test_that to run.

We can run expect_equal on its own:

## Error: 0 not equal to 1.

## 1/1 mismatches

## [1] 0 - 1 == -1but that doesn’t produce a summary of how many tests passed or failed.

Passing a block of code to test_that also allows us to check several things in one test:

## Error: Test failed: 'Testing two things'

## * <text>:3: 0 not equal to 1.

## 1/1 mismatches

## [1] 0 - 1 == -1A block of code is not the same thing as an anonymous function, which is why running this block of code does nothing — the “test” defines a function but doesn’t actually call it:

18.6.4 How should I organize my tests?

Running blocks of tests by hand is a bad practice.

Instead, we should put related tests in files and then put those files in a directory called tests/testthat.

We can then run some or all of those tests with a single command.

To start, create in your cm104 folder, create this file: ./tests/testthat/test_example.R:

library(testthat)

context("Demonstrating the testing library")

test_that("Testing a number with itself", {

expect_equal(0, 0)

expect_equal(-1, -1)

expect_equal(Inf, Inf)

})

test_that("Testing different numbers", {

expect_equal(0, 1)

})

test_that("Testing with a tolerance", {

expect_equal(0, 0.01, tolerance = 0.05, scale = 1)

expect_equal(0, 0.01, tolerance = 0.005, scale = 1)

})The first line loads the testthat package, which gives us our tools.

The call to context on the second line gives this set of tests a name for reporting purposes.

After that, we add as many calls to test_that as we want, each with a name and a block of code.

We can now run this file from within RStudio:

test_dir("tests/testthat")The output should be:

✔ | OK F W S | Context

⠏ | 0 | Skipping rows correctly

✖ | 0 5 | Skipping rows correctly

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

test_determine_skip_rows_a.R:9: failure: The right row is found when there are header rows

`result` not equal to 2.

Lengths differ: 0 is not 1

test_determine_skip_rows_a.R:14: failure: The right row is found when there are header rows and blank lines

`result` not equal to 3.

Lengths differ: 0 is not 1

test_determine_skip_rows_a.R:19: failure: The right row is found when there are no header rows to discard

`result` not equal to 0.

Lengths differ: 0 is not 1

test_determine_skip_rows_a.R:23: failure: No row is found when 'iso3' isn't present

`determine_skip_rows("a1,a2\nb1,b1\n")` did not throw an error.

test_determine_skip_rows_a.R:28: failure: No row is found when 'iso3' is in the wrong place

`determine_skip_rows("stuff,iso3\n")` did not throw an error.

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

⠏ | 0 | Skipping rows correctly

✔ | 5 | Skipping rows correctly

⠏ | 0 | Demonstrating the testing library

✖ | 4 2 | Demonstrating the testing library

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

test_example.R:11: failure: Testing different numbers

0 not equal to 1.

1/1 mismatches

[1] 0 - 1 == -1

test_example.R:16: failure: Testing with a tolerance

0 not equal to 0.01.

1/1 mismatches

[1] 0 - 0.01 == -0.01

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

⠏ | 0 | Finding empty rows

✖ | 1 2 | Finding empty rows

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

test_find_empty_a.R:9: failure: A single non-empty row is not mistakenly detected

`result` not equal to NULL.

Types not compatible: integer is not NULL

test_find_empty_a.R:14: failure: Half-empty rows are not mistakenly detected

`result` not equal to NULL.

Types not compatible: integer is not NULL

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

⠏ | 0 | Finding empty rows

✔ | 3 | Finding empty rows

⠏ | 0 | Testing properties of tibbles

✔ | 1 1 | Testing properties of tibbles

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

test_tibble.R:6: warning: Tibble columns are given the name 'value'

`as.tibble()` is deprecated, use `as_tibble()` (but mind the new semantics).

This warning is displayed once per session.

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

══ Results ════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════

Duration: 0.2 s

OK: 14

Failed: 9

Warnings: 1

Skipped: 0Care is needed when interpreting these results.

There are four test_that calls, but eight actual checks, and the number of successes and failures is counted by recording the latter, not the former.

What then is the purpose of test_that?

Why not just use expect_equal and its kin, such as expect_true, expect_false, expect_length, and so on?

The answer is that it allows us to do one operation and then check several things afterward.

Our tests still aren’t checking anything statistical, but without trustworthy data, our statistics will be meaningless. Tests like these allow our future selves to focus on making new mistakes instead of repeating old ones.

18.6.5 What type of tests can I do with testthat ?

This page has a thorough list of “expectations”. Some useful functions are:

- test_dir(), test_package(), test_check(), is_testing(), testing_package(): Expectation: is returned value less or greater than specified value?

- expect_equal(), expect_equivalent(), expect_identical(), expect_reference(): Expectation: is the object equal to a value?

- expect_length(): Expectation: does a vector have the specified length? … etc

18.6.6 More practice with test_that

The next two sub-sections of the tidynomicon chapter on testing are likely beyond the scope of STAT547, but I highly encourage you to go through on your own time when you’re about to embark on a project for your research!

18.6.7 Summary and key points of testing

- The three built-in levels of conditions are messages, warnings, and errors.

- Programs/scripts can signal these themselves using the functions

message,warning, andstop. - Operations can be placed in a call to the function tryCatch to handle errors.

- Use

testthatto write unit tests for R. - Put tests in files called test_group.R and call them test_something.

- Write tests for data transformation steps (if you can) as well as library functions.

18.7 Additional Resources

- Stat545.com by Jenny Bryan - Tests

- Wickham and Bryan’s R Packages book - Testing chapter

- Tidynomicon by Greg Wilson - [Tests in R]